Bright Eyes: A True Story For Bonfire Season About Rabbits, Death And Fire

Although lifelong bloodthirsty tyrants, my cats Ralph and Shipley will often go through long phases of not killing another living creature. Born into the same litter, yet roughly as different in appearance as a stunted lion would be from an angry monitor lizard, they are both now 14: an age when many country-dwelling cats lose interest in serial decapitation and begin to at least plan a more pacifist retirement. “They’re done now,” I’ll think after several weeks of peace and cleanish carpets then fatally let my guard down and step on half a shrew’s face. Recently the big problem has been rabbits. I’ve managed to save a few of the poor things, thanks to my advanced tackling skills. One escaped and hid behind the freezer and I managed to lure it out, in cartoon fashion, with an old carrot, then plonk it below a hedge. But I’m a person with two books to research and write who likes being outdoors. I can’t just be constantly sitting at home on a state of high alert with a carrot in my hand.

Cats are ardent creatures of habit but they also do not like to get in a rut. All cats only sleep regularly in one place for a month. After that, by law they must move or they stop being cats. They select and switch their abbatoirs with similar fastidiousness. For a spell the dining room served as Ralph and Shipley’s killing floor, then the bathroom, but recently they have preferred the small downstairs room where I keep most of my book collection. A couple of weeks ago I cleaned up a particularly messy headless rabbit corpse on the floor of the book room. I have a fairly poor sense of smell but, even though I scrubbed the carpet with no less vigour than Al Swearengen scrubs a bloodstain on his saloon floor in the TV series Deadwood, I could not subsequently convince myself I’d entirely got rid of the waft. I love my book room. It's full of books, after all, and also has a beautiful, very spooky hare mask on the wall, which was made for my birthday by my friend Mary in 2011. But the room is a cold one with no curtains or double glazing and I don’t go in it much at this time of year. On the ocassions I did go in, I noticed that the smell was getting the opposite of better. On Monday, I admitted to myself that it was time for a more thorough book room investigation.

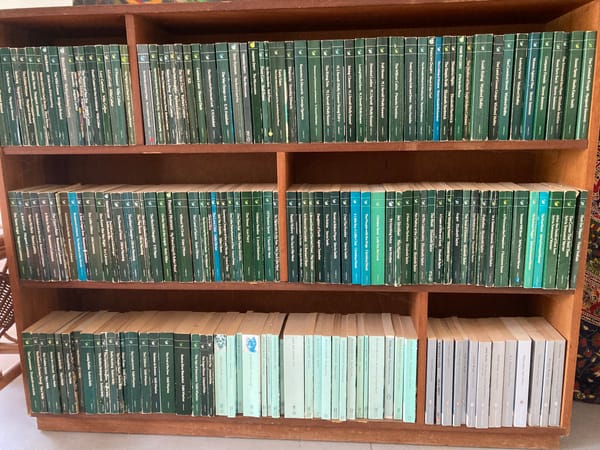

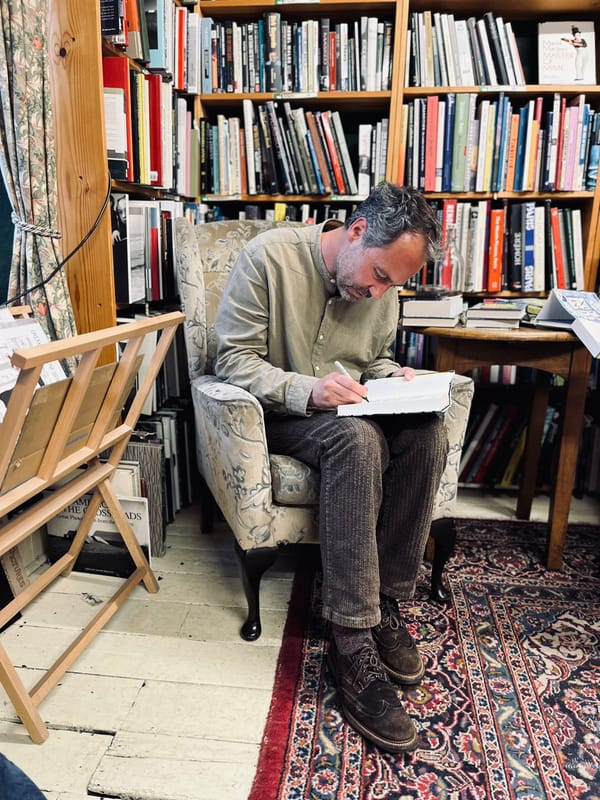

I have made a couple of attempts to stop buying books in the distant past but I’ve since realised it’s an absurd denial of who I fundamentally am as a person. The fact is, books have always been very kind to me and I can’t stand to see them sitting alone in shops, unloved. One day, I’ll probably trap myself behind a book wall forever. But the way I look at it is that I’ll be reading as I starve to death, so it will be okay. My to-read pile spills far beyond the shelves themselves and far beyond sense, teetering in higgledy piggledy piles and on nearby tables. Moving the books to shift the shelving units themselves and get behind them - which, I assumed, was where the smell was coming from, having ruled out everywhere else in the room - is a major operation. My initial investigations uncovered, not too suprisingly, the remains of two dead voles, long since rotted away, but I sensed I was in the middle of a bigger story here and upon moving the fifth and final bookcase I reached its awful climactic scene.

It was a rabbit, I could discern that immediately. But what it really looked like was more like a charcoal illustration of a rabbit ghost, drawn by an artist with a sideline in Satanism. I felt like I’d stepped inside the missing one of Fiver’s nightmare in Watership Down that got cut for being too adult. If I blinked, would it vanish? I tried to think of someone close to me who might come and briefly hold me in a tender way, then leave. Parents? Hundreds of miles away. My mate Seventies Pat? No. He lived in Dudley. The corpse’s edges were indistinct, as if surrounded by an evil vapour. I saw maggots writhing where its brain once had been. An impossible black ooze welded it to the wall and oozed with more determined malevolence as I attempted to move it. The smell was intolerable, like a monolithic forecast of every small awfulness you’ve ever worried would come true. Many years ago a former co-habiter or mine left a pair of horse skulls shut in a big windowed room in summer with devastating results - a story fully detailed in my book Talk To The Tail - but next to this that was like a casual meander around a branch of Lush. As I went back in for a third time with every bit of cleaning equipment I could find in the house, I genuinely began to wonder what would be easier: carrying on in my attempt to save the carpet, or quickly packing a couple of bags and moving to India.

I headed off briskly to the supermarket and returned with more cleaning materials and odour-defusing paraphernalia suggested by friends and my mum: bicarb of soda, coloured biological washing liquid. After four hours, I had rid the room of this dark spectre and its innumerable attendant maggots but it had taken out a mortgage on my part-working nose.

This is the stuff that’s so rarely factored in in the time management of a rural self-employed life with cats: the couple of hours you will fritter away looking for a vole in the bottom of a wardrobe… the thirty minutes it takes to strip the spare bed’s duvet cover and carefully scrape all the chunky dried puke off it… the six and a half hours you will devote to cleansing your house of an unnameable evil. It was almost six pm and I had wasted an entire working day. I knew I should be making up for it by writing into the night but my funeral director friends Ru and Claire had asked me along to their All Souls night ritual at Sharpham Meadow Natural Burial Ground, high above - not that we'd be able to see it tonight - one of the River Dart's most idyllic chicanes. It had been far too long since I’d seen them and the potential nostril transfusion the evening promised was too tempting: hilly night air and woodsmoke replacing the writhing shitfires of hell.

There aren’t many times you find yourself heading to a burial ground to escape the taint of death but this was one of them. I parked and followed two strangers - or, more specifically, the light of the sensible headtorches of two strangers - through a wicker arch and over the brow of a hill to a large fire, surrounded by sixty or seventy people. In the distance the lights of the busy seaside towns Paignton and Brixham twinkled, a seven mile universe away. There is a magic in the air at this darkening time of year, but people tend to overegg it with fancy explosions and the fancy dress of pretend Americans. What this gathering proved was that all you really needed to tease it out it was a strong orange glow and some good barren hills, with hot spiced apple juice as an optional extra.

I remember my friend Adele telling me I should meet Ru and Claire when I first moved to this part of Devon. Was the reason that I did not instantly act decisively upon her suggestion that classic one that makes people shy away from those who work with death: that I did not want them to remind me of my mortality? Possibly. Or maybe it was just because I’m a bit of a forgetful twat. Whatever the case, since Ru tapped me on the shoulder early this year while I was buying crisps and said “Hi! I’m Ru, Adele’s mate, the funeral director!” we’ve been fast friends. The last but one time I saw them they called me into the office of their business, The Green Funeral Company, as I was walking past and asked me to settle an argument about whether a coffin was pretty. Claire thought it was; Ru wasn’t so sure. I took Claire’s side but arguably that was primarily a result of the comparitively low number of coffins I’d seen up close in the past boasting an intricate decorative floral design. Everyone you speak to around here loves Ru and Claire. “Oh, they’re fucking brilliant,” another friend told me not long ago. “They set fire to my nan for me a few years ago.”

What this is is very South West Peninsula, very uninhibited, very self-mocking. What it should not be is erroneously lumped in with any of the area’s more preposterous hippie excesses. There is no room for air quotes during an occasion like tonight’s: the size of the subject matter will wash them away like violent weather. As I warmed myself on the Sharpham bonfire I felt another kind of warmth that I had never quite felt before at any traditional ceremony dealing with death, a powerful breaking down of barriers, a removing of a certain ugliness. Not the ugliness that’s intrinsic to last rites but an unecessary one often on top of it. Ru talked powerfully - in a way that felt universal, passionate and non-formulaic all at the same time - of the souls we were honouring and autumn’s reminder of nature’s ability to die over and over again. He also asked us to spare a thought for the refugees who would not make it across the Mediterranean, and “whose bodies would never be honoured”. Claire and their colleague Jennifer spoke the names of everyone buried on the hillside and amongst them I heard a familar surname that made my chest stop: that of one of my favourite folk musicians. His son. Dead before him, far, far too young.

People were asked to come forward, if they wished, and speak the name of someone they had lost then throw a pine cone into the fire in their memory. I had begun by this point, unbidden, to think of my ferociously loved nan, who died six years ago this week. She'd lived through war and extreme poverty, then, just as her life was improving, the one true love of it - the granddad I never met, and after whom I am named - had been snatched away from her by an arterial explosion in his brain. I had not quite cried at her funeral but I now realised that the moisture pouring out of my eyes was not solely a result of smoke and unfortunate wind direction. I wanted to step forward and add a cone and say something about her amazing kindness, how I’d admired her more every day since I’d lost her, but something stopped me. The people here were speaking the names of relatives and friends buried on this hillside or nearby. Some had died half a century ago, others - including a 21 year-old German man someone’s son had tried and failed to save from drowning in the sea - only last week. Perhaps it was the strength of these stories combined with a sense of geographical separation - my nan grew up in Liverpool and lived out her final years in Nottinghamshire, hundreds of miles from here - that made me hold back. I regretted it. I found myself oddly reluctant to go home, but not just because of that, or dead bunny afterstench. Others seemed the same, as if pinned and mesmerised by the flames. The antithesis of LED light: a healthy, primal hypnosis. The conversation was animated, but during a rare lull I noticed two pine cones still loose, one considerably larger than the other. I picked both up and placed them in the dying fire: one for a big brave gentle life, lovingly remembered, and one for a smaller, fluffier nameless one.