Darkening Days In Summerland: A Personal Compendium

- It doesn’t take a good detective to know why I’m feeling the way I’m feeling right now but, let's face it, I’ve never been anywhere even close to being a good detective; the nearest I get is owning a couple of unusually long coats. I was beating myself up for a few decisions I’d made lately: physically overdoing a house move, going up to the Midlands for a college reunion and coming back with Covid, not being productive enough on my new book due to fatigue brought on by having Covid and physically overdoing a house move, not selling enough of my previous book due to writing it in a disobedient way and avoiding the national media and not having a publisher with lots of money, not writing as many books as I want to due to being on Twitter trying to sell enough of the previous books to make it possible to write more books, not being born into generational wealth... that sort of thing. But then I saw the date: second half of November. Comfortably over the threshold. It’s the same every year. There have been 47 of them now, so you’d think I might have learned by this point, but it would appear not. Extreme levels of self-criticism. Tendency to be even more affected than usual by all the cruelty and brutality in the world. Compulsion to give my body what it nags me for (crisps, wine, hot baths) rather than what it probably needs (water, asparagus, sea). Not connecting with the inherent magic inside great music quite like I normally do. All the archetypal signs I have seen in myself at the beginning of so many winters before. For many other Seasonal Affective Disorder sufferers it’s January and February that are the toughest months, and it's not like I view them as party season or anything, but this is the worst time for me: from that last bit of gold that autumn coughs up, all the way to Winter Solstice. The answer isn’t a special lamp or a diet or a revolutionary change of approach. The answer is remembering you've done this before, that it doesn’t last long, it's utterly necessary, even beneficial, perhaps, and, along the way you should probably be as kind as possible to yourself, because if you’re me, at this time of year, even while you’re trying to be kind to yourself, you’ll inevitably be a bit hard on yourself too - including for being kind to yourself. I find not visiting shops selling shiny new things also helps. I suppose, inevitably, I will have to go into one at some point. Somebody will probably ask me if I am ready for Christmas, and I will politely restrain myself from giving the honest answer, which would be, “Yes, thank you, I am extremely ready for a small but perceptible lengthening of this meagre daylight, not switching the TV on, blocking out the world, getting some serious writing and reading done and eating similar meals to the ones I would eat on most other days, then visiting family members in a casual and very unceremonious way a few days later.”

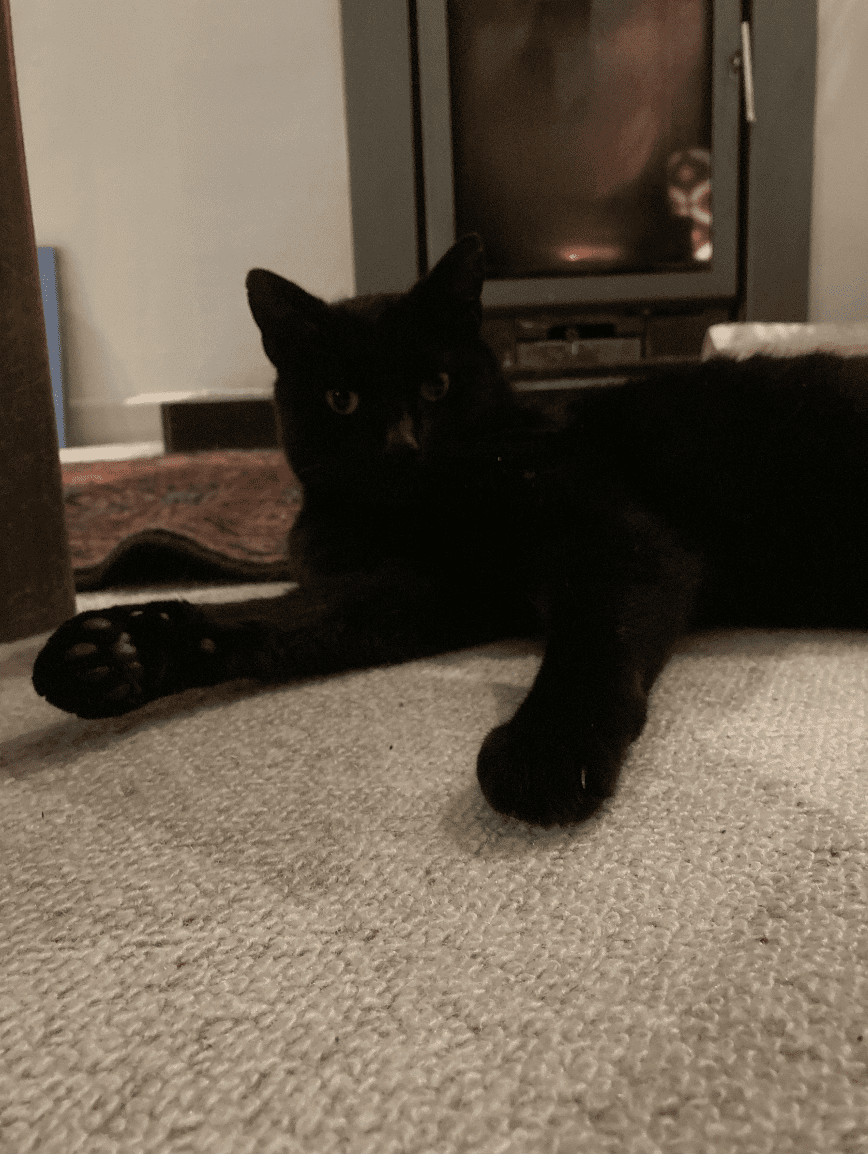

- A black cat showed all the signs of wanting to come and live with us but now appears to have had a change of heart, and that’s been weighing heavily on my winter mind, too. He’d been showing up here sporadically from day one, popping in, nervously grabbing a mouthful of dry food then scarpering. I put ‘Da Capo’, the phenomenal 1966 album by Love, on the stereo and he seemed to be heavily into it. Our neighbour told us he was a stray who’d been hanging around the neighbourhood for a couple of years, and that he was female, which seemed surprising to us, mostly owing to the fact that he was the size of a small sheep. “A lady cat? Are you sure?” I asked. “Well, I assume so, as she has a very high-pitched meow,” our neighbour replied. We soon discovered, though, that despite this gender anomaly, he was definitely male: apart from the shape of the place where his balls had been, there were other telltale clues, such as the fact that he often forgot to close drawers around the house and kept talking about Halfords being his favourite shop. We called him Perceval, and he seemed all at once extremely nervous, extremely affectionate and extremely intelligent. I am guessing he’s about six, but perhaps that’s just me being poetic about it, since it’s half a dozen years since my previous black cats Shipley and The Bear died within a couple of months of one another, and he puts me in mind of a gargantuan hybrid of the pair of them. Like those cats, he has this way of looking like he’d really like to get into it with you, go a bit deeper than just the whole “gaze at my beauty in exchange for warmth/food/strokes” deal. Eleven days ago, he stretched out in front of a rattling woodburner in purring, palpable rhapsody and relief, but hasn’t been seen since two days after that when, while my aunt and uncle were looking after the house, he poked his head through the door, took one look at them, and pegged it. I am trying not to put it down to the bad attitude of our two fully resident cats, Roscoe and Charles, or decide they’ve got anything extreme against him, but yesterday morning I did notice that they'd somehow locked the catflap on the outside. When I go out at night and forlornly call the name that’s his that he does not yet know, the garden, and the woods beyond, seem very very big and empty and dark.

- I got talking to a guy in the building trade, who told me about a secondhand shop where he’d seen an affordable original pressing of the 1968 album ‘The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society’ by The Kinks. I already own a modern repress of it and am far from dissatisfied with its sound but if I get an original I can feel a little closer to history; then when I’m dead and someone is going through my record collection to try to work out how much money it’s going to fetch for a registered wildlife charity they can look at the insert on the disc and say, “Oh my god, this is an original UK pressing. That niche deceased writer who didn’t sell very many of his books really did have a great record collection. He must have genuinely loved and cherished it to make the decision to keep it instead of feeding himself during those pitiful last few weeks of his life.” I drove a significant number of miles to the shop and it was closed. Two days later, when the shop had reopened, I deferred seven or eight important life admin tasks and drove to it again. The record wasn’t there, but a couple of other nice ones I’d been half-looking for, including Dr Octagon’s brilliant ‘Dr Octagonecologyst’ LP from 1996, were and, because I’m me, after an hour or so I found myself in a crypt directly below the shop, rooting through a box of less-exciting-than-I’d hoped baby boomer 7 inches while the shop owner talked excitably with another customer about secondhand firearms. After about three minutes, I was keen to leave, but I wasn’t totally sure how to get out, and the blokes talking about secondhand firearms stayed absolutely rigid about not giving up a millimetre of space in the flow of their conversation. At one point, I found myself inadvertently beginning to put my hand up, as an eight year-old suddenly, painfully desperate for the toilet might in order to gain the attention of a teacher. What I wanted to say to the vintage gun enthusiasts was “For fuck’s sake please can you stop talking about guns just for ten seconds and let me out?” but instead I pretended to be more interested than I was in some late 19th Century chimney pots and waited another ten minutes until they finally paused and gave me a chance to speak, and now the rest of my life is delayed as a result, and will be forever. “How do you get yourself in these situations?” a couple of people I've told about the incident have asked. As record hunting misadventures go, I personally didn’t put the experience in the class of notably disturbing, but that’s potentially all about context. The previous week a man selling some rare blues and soul LPs had asked me to meet him in a cemetery, then led me to a barn full of vinyl in an undisclosed rural location, attempted to recruit me for a notorious far right political party and opened up his shirt to show me his colostomy bag.

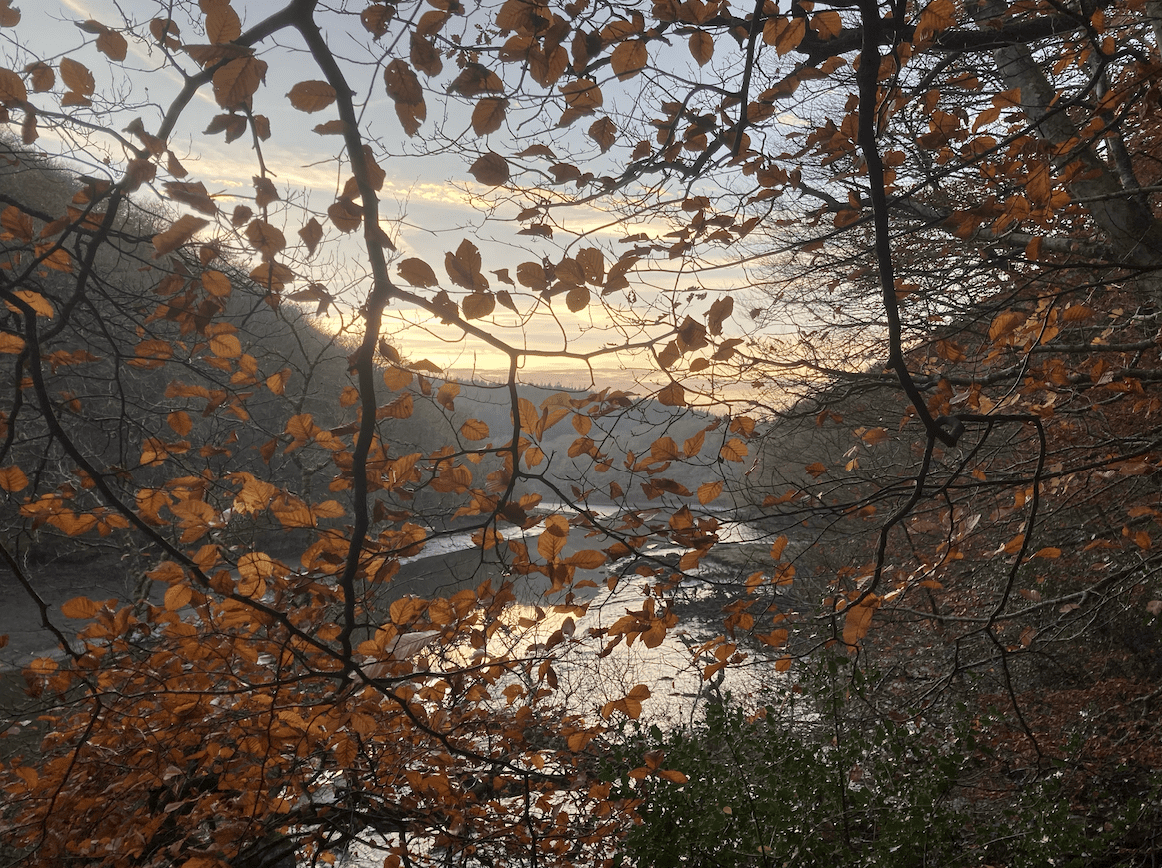

- The light is brief but I love what there is right now, on a fine bright day in the valley where I live close to the south coast of Cornwall and feel lucky to be inside it. It’s very different to the light where we came here from, in south Devon, far more sequined and pink than the muddy yet stark light on the nearest part of the north coast (which, because I still have my Devon brain on, I am constantly shocked to find is only 45 minutes away by car). The sun and I have not long been up today and, ever since we have, I have felt, up here on the hill, like I am part of an evolving sky. Before the sun properly poked through and started its interplay with that last bit of gold in the trees, one shaft of it directly lit up the huge manor house on the other side of the valley, reminding you that when rich people built their houses a couple of centuries ago, they really thought about it, and didn’t decide to just plonk them anywhere that happened to be going spare and wasn’t too close to the communal village bog or a major arterial road. The light truly is unique in this southernmost county of the UK, just as the painters of the 1800s who were inexorably drawn to it noticed. I enjoy making the most of it, in the solid half an hour you get between sunrise and sunset at this time of year. I wonder if I will at some point begin to feel less like someone on a long holiday, less like someone on a break between removal vans and correspondence with the Deposit Protection Scheme. I walked along the river at dusk and saw lightbulbs clicking on in the houses on the banks. “I would love to live in a place like this: Wouldn’t that be great?” I thought, walking towards a front door nestled between those terraces of glowing lightbulbs then opening the front door. I came back out, collected some logs, slipped on the moss near the wood store, styled it out with a quasi breakdacing move. “It’s fine – I’m unhurt,” I assured the night. The last blushing clouds fell below the hill and owls came out in force, stronger than before. One sounded like it was in the bathroom. “Is there an owl in the bathroom?” I asked my girlfriend. “No, it’s just me,” she replied. “Are you sure?” I said. I’d had my suspicions for a while and this latest turn of events was doing nothing to put them to rest. I opened the back door, and the owl in question, clearly an experienced and comfortable ventriloquist, flew from the branch of a dead tree over my head. He was a male. I could tell. The signs were there in his very deep voice. His flight was kind of groovy, a dance, like some dude in a hip club, 1968 or maybe a little later, sidling up, checking you out, taking his time, getting plenty of evidence before making his move, which he would somehow shape into something that didn’t resemble a move at all.

- You can’t relocate from winter to summer but that doesn’t stop me from giving it my best shot: perhaps that is why I currently find myself living further down the right boot of the UK than I ever have before. In a 1908 poster advertising campaign, using a painting that highlighted the topgraphical commonalities between both places, Great Western Railways promoted the “great similarity” between Cornwall and Italy in “shape, climate and natural beauties.” A few weeks ago, in the midst of a fortnight of constant sideways rain, I walked several shivering miles from my bungalow in the UK's answer to mid Tuscany, past an isolated stall selling some soggy cabbage, to the nearest train station. The train was cancelled, my phone had so much water in it that it had stopped working and wouldn’t tell me when the next one was, so I walked home and had a nice hot bath. Back in the first half of the 1900s, there were branch lines everywhere around here: I look at the railway maps from that era and it’s no less exciting than looking at a hand-drawn guide to the locations of several trunks of buried treasure. The poster art, of course, offers an extra, heightened filter for the fantasy: the work of the likes of Charles McKnight Cauffer and Edward Cusden sending you tumbling into a subtly abstract dreamland where rugged landscape intersects with engineering brilliance. How much do I want to be a painter of vorticist railway art in 1928? Probably even more than I want to be a creative person in any of the other eras I fantasise slightly unrealistically about living in. But what isn’t unrealistic is looking back to the time of the branch lines and seeing the option of a better, less isolating, less environmentally costly future, aka a better now: the one that we were denied in the name of greed masquerading – as it so often does - as ‘progress’ when British Railways Chairman Richard Beeching and Conservative Minister for Transport Ernest Marples (who'd uncoincidentally had financial stakes in the success of the M1 motorway) ordered the closure of a third of Britain's railway lines during the early 1960s. When I ask myself what my favourite memories of the travel I did as a young adult in the UK were, I discover that none of it involved a car. It’s taking cheap trains through Yorkshire and Cumbria and County Durham and Northumberland and The Scottish Borders and getting into conversations with strangers, frequently of the old and wise kind. It’s standing on a tiny platform, hungover, after celebrating the turn of the Millennium, and having to flag a train down because of the backwater nature of the station. I now drive the road leading to and from Brunel’s bolshy railway bridge across the Tamar from the fattest part of Cornwall and think of the bloke in a white camper this time a year ago who boxed me in and yelled, redfaced, at me for driving too slow, think of a few weeks ago when I found out I had Covid then, hours later, as I was - due to said Covid - prematurely returning the van I’d hired for the house move, its cam belt broke and left me stranded on a hairpin bend, as rush hour traffic hurtled past me or - as it seemed at the time, in my dazed and coughing state - at me. I travel roughly the same stretch of land by rail and the train passes serenely over viaducts, allowing plenty of time to admire a half-completed jigsaw of fascinating secret land chunks in the estuaries beyond Plymouth. Maybe someone nearby eats a packet of McCoys in an antisocial fashion, or has an annoying child, or bickers with their spouse a little too publicly on their phone, but that is what headphones and audiobooks and Afrofunk playlists are for. Progress can be pretty great sometimes. I want to ditch my car, let it pass into the hands of someone who won't feel burdened by its concomitant stresses. I barely even known what it's called. I am, however, not yet that brave, and I cannot discount all the fascinating carless places it has permitted me to explore. I am a walker, and I am a walker in 2022, not 1932, or some other parallel, less technologically ruined version of 2022.

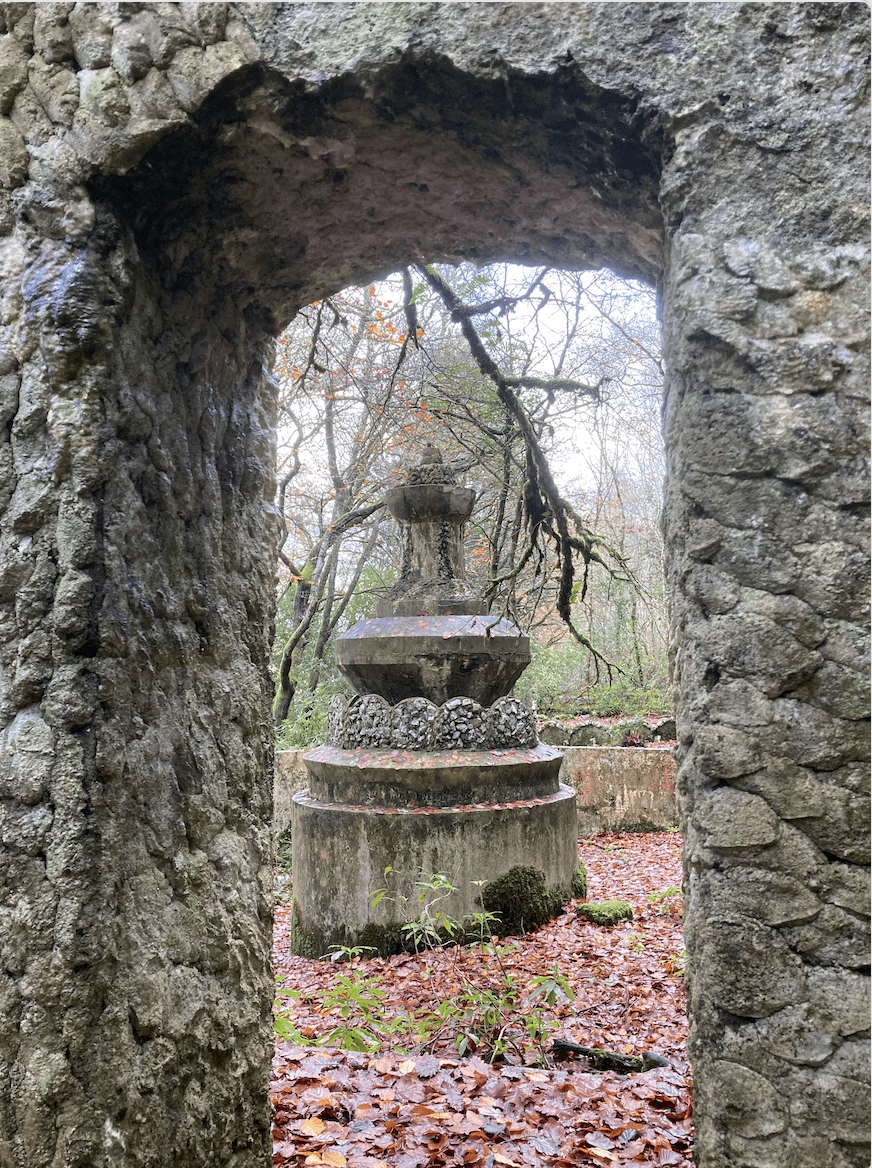

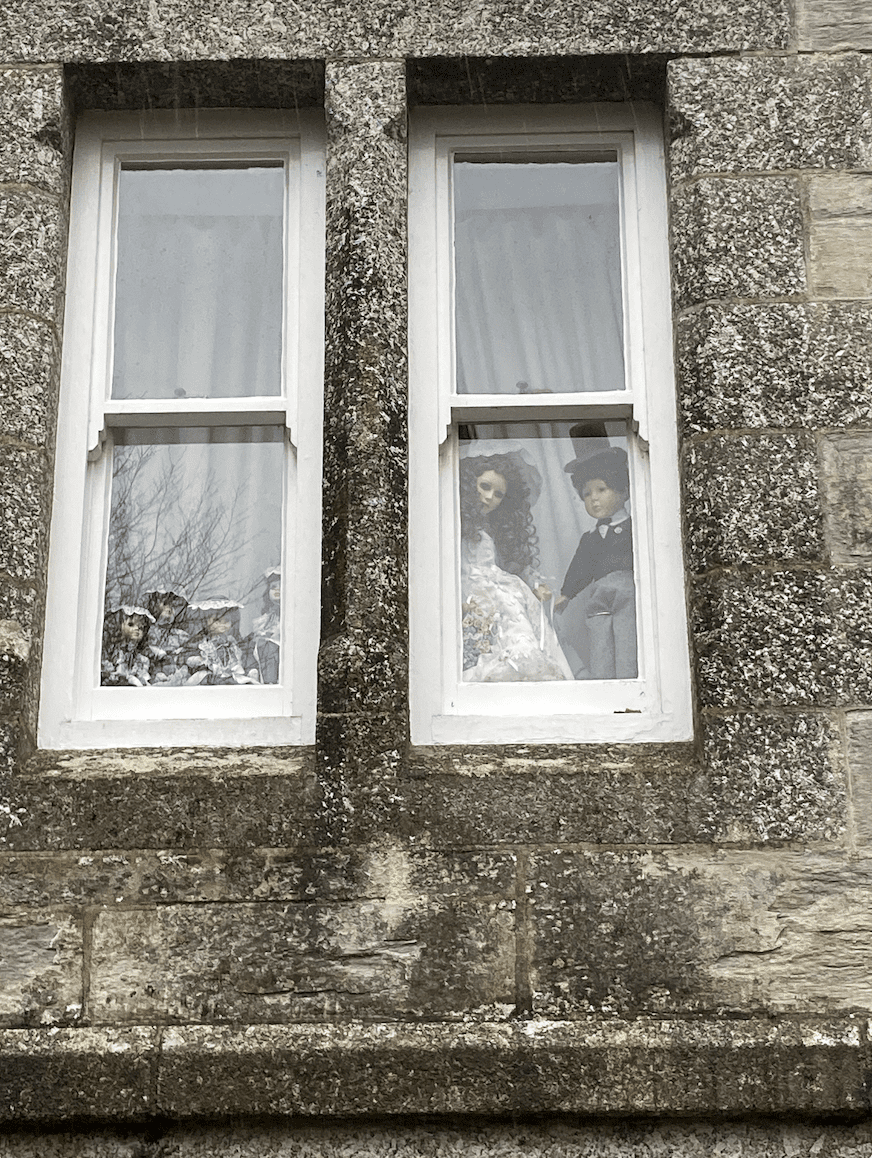

- Yet it is surprisingly easy to hypnotise yourself into a pre-WW II fantasy around here, especially at this tourism-unfriendly time of year. Most of the lanes behind our village don’t technically go anywhere, fading out to wild clematis and mud at lonely farms and dark cottages with windows obscured by ivy and front doors in a state that makes you about 50/50 regarding whether any living being still resides behind them. This is not the Cornwall you see in the air b&b ads. Several Victorian dolls stare at me, their faces pressed against the upper window of a gatehouse. They’ve been arranged to look outwards, like prisoners begging for help before their remorseless captor returns. I walk along the river, past a house built a century or so ago, with no road or track leading to it, all the materials required to construct it having been transported by boat. A few hills away is the much grander building where, in the 1930s, Daphne du Maurier began to write her novels of quiet creeks, slipped time and vast, bedevilled homes. I branch off from the main river onto the banks of another, which becomes a thin channel as I move inland. From above, not long ago, I watched open-mouthed as skeins of Canada Geese followed the precise curve of it, against a sky like freshly applied blusher. A telephone engineer told me the Red Arrow planes used to do the same thing, but I will happily stick with the geese. In the mud below me as I walk is a large rectangular can with ‘GENERAL PURPOSE RESIN' written on it, the only litter the receding tide has revealed. Even it – the shade of yellow, the typography – looks kind of midcentury. Further on are the rewilded remains of a pleasure garden built in the 1920s by a renowned local clay magnate: bandstand, granite arches, swimming pool, fountains, heavy atmosphere. Boat people held decadent parties here and races on a 200 metre running track now submerged beneath foliage. King Edward stopped by in the midst of a Cornish break during which he also “besported himself with young ladies”. I am aware, as I walk through what is left of the pleasure garden, that if I were a character in a 1970s BBC Play For Today, I would be no doubt be spinning in circles, as ghostly laughter, maybe mixed in with the crying of a distressed spectral child, rang out all around me. A month ago, at dusk, on a path directly above this place, further into the torso of the forest, I saw a woman disguised as a sapling, scuttling into the undergrowth: an incident I have still not got to the bottom of, despite making enquiries at the post office. The sun is doing that thing it does at this time on a winter afternoon when it looks like a dazzling portal that’s opened up deep in that part of the woodland you can’t quite reach. I’m getting that feeling again: that one of profound envy for people who live around here. It’s almost fully dark when I get home and I switch on a couple of the lamps that people see defining the walls of the valley when they travel along the river road between 4pm and midnight. I am looking forward to spring: perhaps more so than I’ve looked forward to any spring in the past. But I seem to say that every year, then forget that I have.

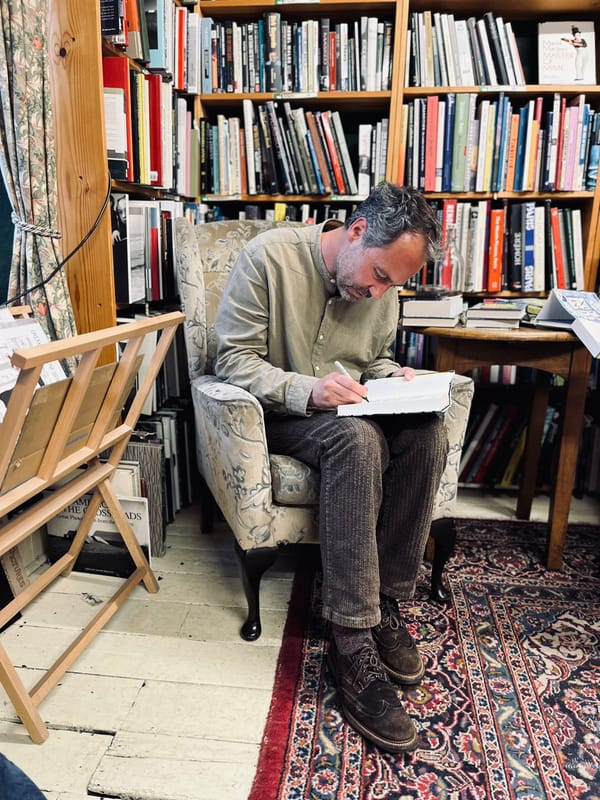

My latest book, Villager, is available here from Blackwells with free worldwide delivery. If you are in the UK, I also have a few first edition hardbacks here at home to sell for £16.99 cover price plus p&P, with a free print by my mum, Jo. Please email me via this link if you'd like to snap one up while they are around. Very happy to sign and dedicate them personally, too.

All the writing on this site appears free of charge but you can subscribe to it and help support it via the homepage, if you choose. Every donation is much appreciated, and helps keep writing appearing here more regularly.