One winter I discovered that winter is the perfect time to listen to unvarnished British folk songs that get down to the stark bones of what it is to be human and since then in winter I have never stopped discovering the same fact.

One winter I mistimed an afternoon walk and completed the last two miles of it after the sun had vanished beneath the long edge of the land. My route took me past a Bronze Age burial mound which gave me an idea for a novel that I was not yet capable of writing.

One winter on a much longer walk in hillier country I looked across towards a hedge and saw a strip of black binliner caught in the top of it, which is a concept known in Ireland as “witches’ knickers” but in this case did not look like witches’ knickers. It looked like The Devil, reclining amongst the thin twigs, idly watching my progress through one hollowed out eye.

One winter I lived in a unique house by a river which was full of dark magic and bad insulation and which, given the opportunity, I might well have lived in forever. Because of the bad insulation and the river and the height of the living room ceiling and the biting winds indelibly associated with the region I would get up at around six to light the log fire then usually keep it going for the whole day, during which I would feel palpably aware of the house’s checkered history of troubled tenants, without quite knowing it. The fire was blazing at the party I had that year and the room was warmer than I’d ever known it to be because several bodies were in it. Michael said he was going to check out the river, as there was fog rising from the ice forming on its surface, and he thought it would be good for what he called a Mystic Moment. I considered putting the song Smoke On The Water on as it would have been apt but it seemed too cheesy to do so and besides it was far from my favourite Deep Purple song: less a song and more a strong riff pulling a song behind it, in the way an expensive car pulls a cheap caravan with a broken wheel arch. Michael opened the window then stepped out into the cold foggy air, perhaps believing he could walk on water, or more likely believing he would find a supporting balcony below him, and Karl and I grabbed one of his legs each just in time to avert disaster, and not long afterwards Michael’s band went on to make their most dark and imaginative record yet, which might transpire to get its dues from a distant future generation but was far too good in its own particular way to sell a really large amount of copies upon release.

One winter I got utterly, fantastically lost in the TV series Box Of Delights to the extent that each time an episode of it was on I forgot my name and where I lived, and spent the cosy curtained early evenings on either side of it covered in glitter making Christmas decorations and cards with my mum, never realising it was the last winter in history when I would ever still feel properly like a child.

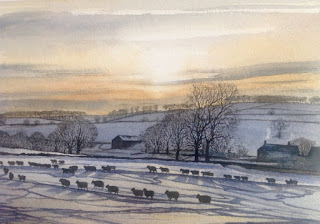

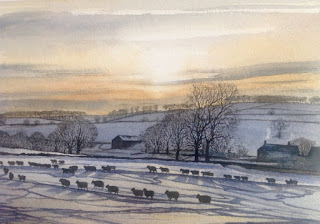

One winter we moved from a mortgaged house my dad grew to detest on an estate where all the other houses except ours seemed to have been burgled to a rented house in the countryside that my dad loved which did get burgled. A week before we moved in my dad drove to the rented house alone in the snow with some canvas, some paint brushes and acrylic paints and sat in an upstairs room of the house with a blanket on his lap painting the white valley he could see through the window in front of him.

One winter I returned from an encounter with some emotionally cold people and couldn’t seem to get warm and get on with my day, no matter how hard I tried. I gave up and got into bed with an old hot water bottle and spent several hours reading John Irving’s novel The Hotel New Hampshire and have rarely felt more content.

One winter I fell asleep on top of the same hot water bottle, which was by now even older, and it seriously burned my leg. The burn turned into an unsightly, furious blister and left a large scar, still clearly visible today when I am trouserless, which hints at a far more heroic backstory.

One winter I walked with Will and Mary past ice age pond-swamps and hairy cows that watched us dolefully from dark woods and we cracked the natural frosted glass skin on puddles with our heels and at the end of the walk we all admired the way the sun looked against the low white-red sky then realised it was actually the moon, not the sun.

One winter - well, actually it was spring, but it was a cold day, and felt like spring experiencing accelerated nostalgia for winter - I walked back from the pub with Pat and Rachel and Pat told us to look at the moon, which was shining amazingly brightly through the trees, and Rachel and I waited a minute or two before explaining to Pat that it was actually a streetlight, not the moon.

One winter I saw you on the path near town by the river, where I’d last seen you, in summer, when you’d smiled and said hello and, because I was talking on my mobile phone at the time to someone close to me about their hospital appointment, I’d not responded in the way I felt instantly compelled to. And now - we were heading in the opposite directions to the last time, in twice as many clothes, but in almost exactly the same spot - I did say hello, and you did too, and we both smiled and reduced our walks to slow motion for a split second as we passed and for some baffling reason, not even shyness, I didn’t stop to introduce myself and, even though I’ve decided lately that I don’t have regrets, that the experiences they normally centre around are life’s most strengthening and character-forming, ultimately rendering them redundant as a concept, I know that’s not quite true, because four days later I am an unchanged person and still regretting my decision to keep walking.

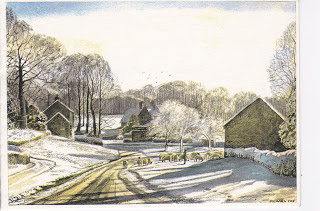

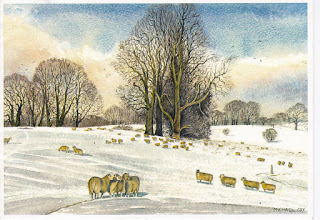

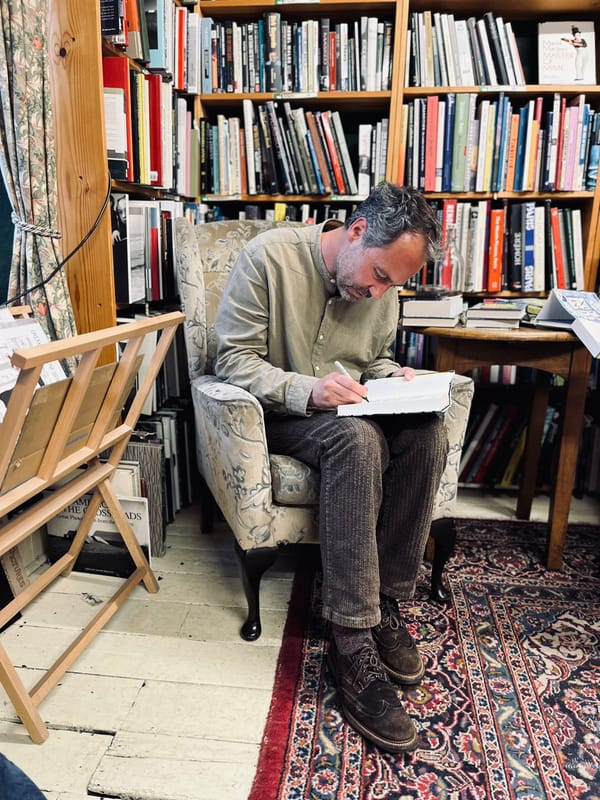

Paintings of winter in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire by my dad.

This piece was inspired by the Nicholson Baker essay One Summer, from his 2012 book The Way The World Works.

I don't write for any mainstream media publications and chose to put my writing on this site instead: around 200,000 words of it so far. It's all free, but if you feel like donating a small monthly amount to help me keep going, you can do so either by paypal or GoCardless. You'll also find a subscription link on the home page if you'd like to sign up to be notified when a new piece is published.