The Place My Voice And I Are From: A Few Words On Accents

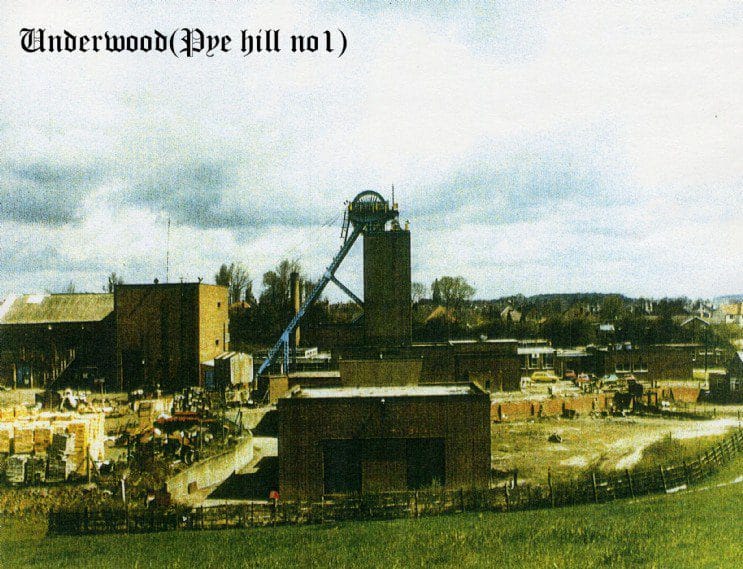

I am from a Place, but I have been around a bit, so maybe the truth is that I am from lots of Places now. I am also not originally from a Place in the way that some people are from a Place. I am not from a Place in the same way that my mum, who is from Liverpool, is from a Place. I am not from a Place in the same way my friend Pat, who is from The Black Country, is from a Place. Where I am from, if we are talking about the first two decades of my life, is an Almost Place: not the middle of the middle, but the end of the middle, not even quite conspicuous for its middleness. For people who live in southern Britain, the distinction might not be important; for me, or people from just north of where I’m from, it’s crucial. All my mum and dad had to do in 1975 was buy a house 20 miles further up the country’s oesophagus, in an area that really didn’t look all that different to ours, with its similarly large quota of pebbledash terraces, spoil heaps, chip shops and miners’ welfares, and it would all be so much more clear cut. I don’t quite feel like a card-carrying midlander but if I claimed to be a northerner to, say, my Sheffield friends, who live not much more than half an hour north of where I went to school, they’d laugh me out of the room. It’s the same place, but it’s also not. If you listen closely you can hear signs of it in my accent, such as the fact that my accent sounds like nails scraping on the walls of Yorkshire, asking to be let in. It’s been softened a lot, sanded down by years of living in East Anglia and the South West, years of living with and around southerners, but it’s still very much there. Posh people from anywhere south of Birmingham think I sound northern. Non-posh people from anywhere north of that think I don’t. It’s all part of the confusion of being from the End Of The Middle. It’s also an aspect of the larger complexity of life on a small island where, wonderfully, you can drive ten minutes up a road and hear voices that sound like they’re from a different planet. We joke about accents in Britain but they are a more heated topic than we will admit. When we discuss them, we discover that we are essentially still the people we were two centuries ago, locked proudly into the culture of our own village and rarely leaving it.

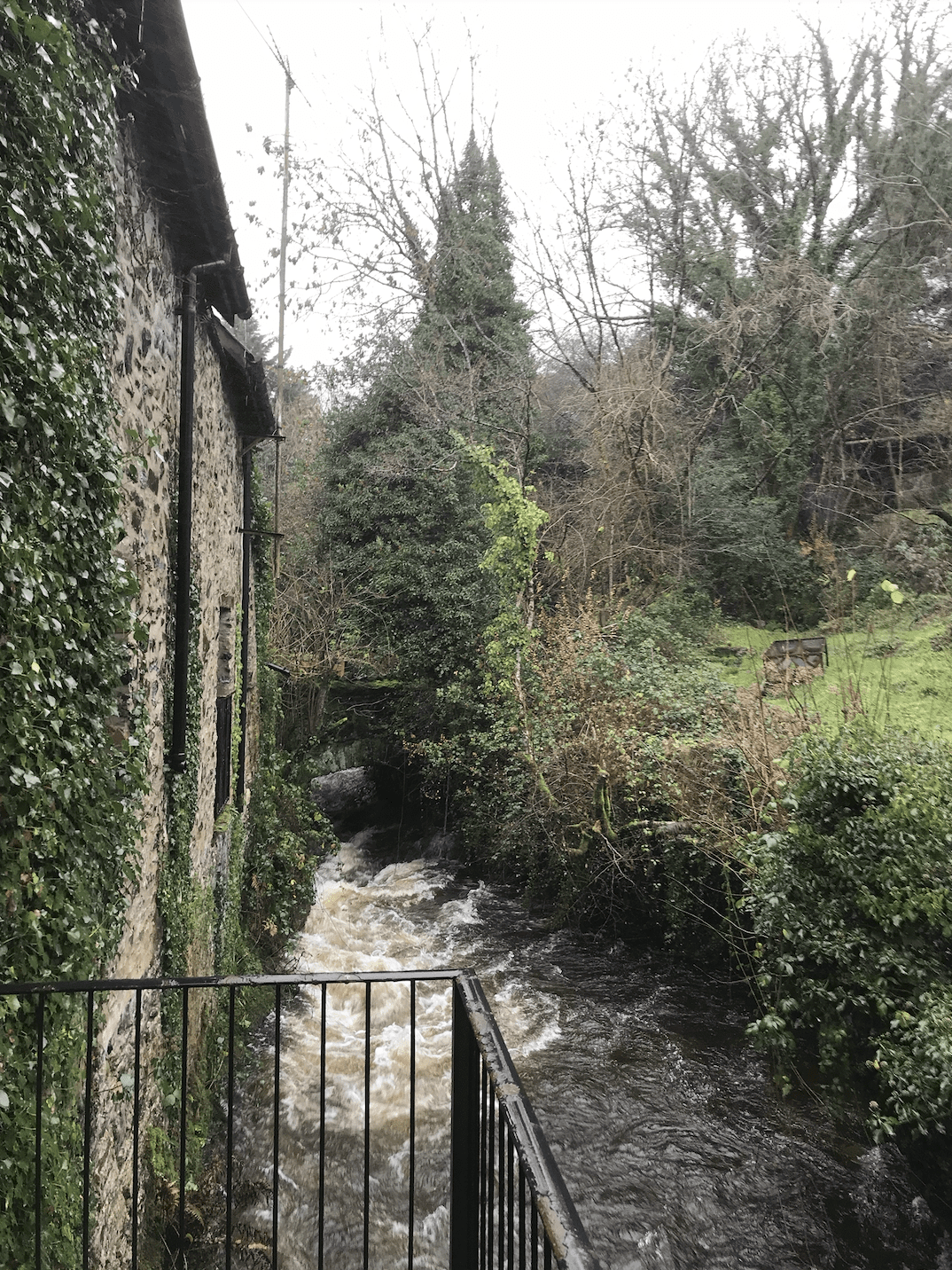

I know what I used to sound like. I can have a listen if I want to remind myself, since what I used to sound like is preserved on a VHS tape recorded when I was 16. There is nothing more illustrative of the softening of my accent to me than meeting up with the Nottingham friends I still know from that period, who good-naturedly ripped the piss because I sounded “Yorkshire” and “like a farmer” to their ears back then, and realising that in the two decades I’ve been away someone has flipped the picture: to me, they are now the ones with the coal and strong tea in their voices. But there is a difference: their accents are undiluted Nottingham; mine is North Nottinghamshire, made less gritty by my time away. It's a disused colliery where grass and four or five trees have grown, masking the iron ore underneath. It also retains just the faintest hint of passive Merseyside, owing to the fact that it’s where most of my blood relatives - my mum’s side of the family - are from.

My dad’s accent is stronger than mine but it’s marginally more southern than mine, more Nottingham, less North Nottinghamshire-Derbyshire border, more factory, less pit. Growing up, as he greeted me with phrases such as “ALL RIGHT, YOTH?” and “ET'S LET’S ‘AY A GLEG”, I was barely aware he had any accent at all. That’s what will happen when you live in the End Of The Middle and manage to go until just after your nineteenth birthday without meeting a properly upper middle-class, university-educated person from southern England. To me, Nottingham was the refined southern accent in my immediate life, with the exception of perhaps Leicester, but Leicester didn’t really count, as it was way down south, over 40 miles away, and you only went there on special occasions.

By my mid-20s, I was obviously still sounding comically common and upcountry to some of the privately educated newspaper editors I was working for. “‘’Ey up, Tum!” one would say in a slightly off parody of a Nearly Northern accent when he answered the phone to me: a joke that, at least to his ears, never got old. Prior to nervously recording a segment for an arts show on the BBC, I was offered an elocution lesson so listeners would find it easier to understand me. After the show was broadcast, I was told the presenter thought me a “new and different voice”. What he meant, I now realise, is that unlike most of the other people who appeared on the show, I sounded a bit working class and northern in a hard-to-pinpoint way. I have never consciously tried to change my accent and it makes me a little sad to think that when I was younger and a little less sure of myself any of these experiences might have had any insidious impact on the way I spoke. Before I moved from Devon to the Peak District in December, 2017, I could feel my accent rushing back, doing a happy jig in my larynx at the knowledge that it might soon be free again. I have no doubt that if I’d decided to stay in the Peak long term, instead of moving back to the South West, it would have returned unabashed, perhaps even gaining a new overcoat in the process. Ultimately, I don’t feel that the old, missing parts of my accent have vanished; it’s more that they’re just napping. It only usually only takes a couple of drinks, or time spent with people from my homeland, to wake them up.

You can hear my voice on the audio version of my book 21st-Century Yokel here.

I don't write for any mainstream media publications and chose to put my writing on this site instead: around 200,000 words of it so far. It's all free, but if you feel like donating a small monthly amount to help me keep going, you can do so either by paypal or GoCardless. You'll also find a subscription link on the home page if you'd like to sign up to be notified when a new piece is published.

My latest book is called Help The Witch. I have a few signed copies of it here: if you'd like to order one of these direct from me, email me via this form.

My new non-fiction book, Ring The Hill, is now funding for autumn 2019 publication.